As a personal rule, I don’t engage in political debate on Facebook. Not that I think it is wrong, but it simply isn’t viable: Hard to carry on a conversation that doesn’t end up in some kind of debate—and often with people you don’t even know and you wonder how in the world they ended up on your friends’ list. I don't mind if people know what I think on issues or who I’m voting for (Obama).

A few weeks ago I shared what I considered to be a clarifying chart on FB. Frankly, I was getting really tired of the lies that the Republicans are telling about the last four years—apparently believing that President Obama is the first president of the United States because everything that is wrong with the economy is, directly, personally his fault and, apparently, there were no problems before him. No wars. No defense spending. No rising oil prices. Everyone had a meaningful, personally fulfilling, and highly paid job. We lived in some sort of Garden of Eden, I guess. Who was that president before Obama and which party was in control of Congress? Hmmm.

So, I posted it and suddenly a chart about the job situation before and after Obama resulted in a debate about abortion and a variety of other women’s justice issues. I kept out of it because, well, the argument was beyond my sense of the kind of discourse that I think is reasonable on FB…. But things continue to spiral down and, honestly, I’m pretty disturbed by the language and attitudes of some of my friends. I get that this election matters—and I get that people who believe differently about important issues and offices can differ. But there is a “Christian” meanness that creeps in that has lead me to hide many of those comments because I just don’t want to be associated with them. Having comments on my FB pages that suggest that Obama is in some sense not Christian—maybe even anti-Christian—and that the Republican agenda is the Jesus agenda; well, I just can’t accept it. Meanness is not a Christian virtue, and confusing political agenda with Jesus’ message leads to such deep confusion among those in the “family” and watching the “family” seem simply (actually complicatedly) wrong.

I do not mean by that statement that I think my faith does not factor into my voting. Of course it does. To the best of my ability and understanding, I want my convictions about what it means to be a follower of Jesus to deeply, even primarily, influence how I mark my ballots. Honestly, to a large extent I am a registered Democrat because of my understanding of what Jesus teaches about how to follow him. But I do not confuse the two; neither do I conflate them. Neither do I think that America is about one religious perspective dominating all other perspectives—there’s something fundamentally un-American about that. I am never confused about the absolute difference between being a follower of Jesus and an American—Jesus said to Pilate, “My kingdom is not a worldly kingdom” and it is to his reign that I am bound. I am not confused about this.

But these are what I’m confused about:

Along with many of my friends, FB and otherwise, I am “pro-life.” What I mean by “pro-life,” however, is this: I am a pacifist; I stand against the death penalty; I believe schools should teach responsible sexual behavior even as they promote abstinence; I believe in providing universal health care for all persons so that all persons are able to lead healthy lives. I do not think you can be pro-life about only one thing and anti-life in others. Jesus calls us to love our neighbors—even when our neighbor is an enemy.

In addition, I don't believe that taking a stance for pro-life requires condemnation—especially mean spirited condemnation of those who believe differently. While I stand in one place in principle, I cannot make decisions that require everyone else to live by my principles—I am not they and I do not know their situation. In other words, my pro-life stance does not allow me to say that abortion is always wrong—nor can I insist that no one should ever be allowed to. Jesus entered into personal relationship with folks of every stripe and invited them to be better than they were; still does that. By drawing the kind of hard lines so many of us draw about acceptable and unacceptable behavior—how is that inviting people into relationship with Jesus?

I’m also confused about the health care debate. Anything that extends health coverage to the most people should not be a political debate; really, for anyone’s neediness to be devalued and ignored and not served seems to me be essentially not Christian. Even Jesus had to be corrected about this—by a woman seeking control over her own body. People in need are people in need (Jesus interrupted just about anything that he was doing to respond to need); to reduce human neediness to political agenda is wrong.

I’m also confused about the education debate. Anything that helps anyone grow in ability to live in this world in meaningful and skillful ways should not be the subject of political debate. We spend untold billions on death; we spend so little on helping people become better people. I do not mean to suggest that the solution to the crisis in public school education can be solved simply with more money. Frankly, I think much of the struggle in our public school system today is because Christians have abandoned them. What sense does it make to remove Christians from some of the neediest places on earth?

I’m also confused about the anger and meanness that flows through conversations about homosexuality. When Jesus told us to love our enemies and love the stranger and take care of our neighbor, I don’t think he was suggesting that we could somehow pick and choose. All persons are valuable. All persons are image bearers. All persons are loved by God. All. Other than the religious leaders of his day—the hard liners who were grateful that they were better than everyone else, especially women—Jesus had only acceptance and welcome and health, even (or especially) when it invited condemnation and accusation. How can we be otherwise—regardless of what we might believe about sexual identity and orientation.

I’m also confused about how we work so hard to exclude people from our country. I remember the day that I realized that on my father’s side of the family, I’m first generation American. My Dad was an immigrant. Actually, so was my Mom’s family, just more generations back. I think we allow our fears to dominate us and create these fences to protect ourselves, creating some sort of false security. Jesus invites us to consider our neighbor—and defines neighbor in the most inclusive terms. Recently in class we were talking about the parable of the Good Samaritan and thinking about the usual stuff. Then, inspiration struck, and I asked: what are we not told? What we are not told is who the man in the gutter is—we know nothing about him but the circumstances of his immediate situation. He is robbed, beaten, left for dead, and naked. He could be anyone, a student said; yes, I said: anyone. That’s pretty inclusive; not much basis there for excluding anyone from the definition of neighbor: the person in need.

Well, I’m sure this will create some kind of debate and that persons out there, even some of the ones who know me well, will dismiss this as Arthur’s usual weirdness. This is stuff, however, that will not leave me alone. I simply mean to invite my Christian friends to spend more time paying attention to Jesus, quit asking what he would do, start asking what he did do—and work really hard at adjusting your political agenda to be one that expresses what Christians say in church about our loving and forgiving and gracious God.

I know that won’t happen because many of you already think that’s what you are doing; so, my final request is this: please quit the meanness!

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Monday, October 29, 2012

Third cup: Thinking about teaching....

I’m reading a biography about Leonardo da Vinci (Bramly, Serge. (1994) Leonardo, The Artist and the Man. London: Penguin Books). I’ve long been interested in him—who hasn’t—and decided that I wanted to know more, although apparently there is not a great deal to know for sure. Even though this book is 420 pages, excluding notes and index, for someone so well known and so widely recognized, most of his life is subject to serious, scholarly speculation. What is known for sure, however, is certainly justifiably the basis for describing him as genius.

This is not, however, what I want to write about. Read this from Bramly:

It may seem extraordinary to us that artists of dissimilar and often unequal talents should collaborate on a work. But in Leonardo’s time, a painting was sold in advance, and the painter was working not for himself but on commission. The artist was not yet inspired by an irresistible desire to express himself, his work was not the flesh of his flesh, however great the effort or the passion he put into it: it only have belonged to him (202).

Today, we attach a far more clean-cut—and therefore narrowly proprietorial—notion to the work of art. There was no such thing as artistic property in those days, and I do not think that Leonardo would have minded at all that his style and his ‘concepts’ were divulged to others.… I would say that Leonardo … was something like a famous dress designer in our day who designs for both haute couture and the ready-to-wear market; he may grant licenses to use his name but is not always protected against plagiarism. … At the end of the day, Leonardo would have been perfectly satisfied: his followers would be helping to make his vision known, promoting his reputation, even ‘advertising’ his work.… (203).

So not modern! Ownership of a work matters less than the collaboration that produces the work. Amazing.

This took me back to the olden days of the Culture of Western Man (CWM) program at WPC. (For those of you who don’t know about this: CWM was a two-year interdisciplinary general studies program designed around great questions—“Can man opt out?”—that integrated nearly all of the traditional liberal arts core courses into one focused combination of lectures, readings, and discussion groups.) Clearly the architecture of this brilliant and terribly unwieldy interdisciplinary general studies program clearly belongs to Marshall Christensen; this amazing complexity of important and life-changing questions would guide a lifetime of study. The actual building and then living inside that architecture, however, was one of the most shared and collaborative ventures of my life in academia—perhaps in my whole life. Several of us, sitting around the table, working together to build out the design, carefully assuring appropriate disciplinary contributions while assuring equally that a broader, “live the big questions” rubric was kept supreme.

Beyond that, I think for the first time for most of us "CWM profs" were together in the classroom. I am sure that it was the first time for such an extended period. When I lectured about myth, the whole faculty was present along with the student body; when Charles Nielsen lectured about economic materialism, the whole faculty was present along with the whole student body. We listened to each other and talked with each other and questioned and critiqued each other. It was, for me, a truly collaborative—and transforming—experience.

It was genius, I think. It was a distinctive, nearly unique program that might have survived in another setting. I think WPC lacked the reputation, the finances, the standing to pull it off in relationship to other schools, struggling always to explain to registrars and dean and advisors how this effort broke down into traditional academic credits. I think we lacked simply the number of faculty to sustain this two-year mega effort. While I think the humanities core currently offered at WPC is a strong and thriving program that clearly channels the spirit of CWM, I am sorry it didn’t survive; I am grateful to be part of a grand experiment. It was a transformational work for me—personally and professionally.

Collaborative education is something WPC still works at; I think, however, it needs more attention. Building silos is easier and requires less work than building barns, which always require collaborative conversation about how to make a barn achieve its whole function under one roof.

Friday, October 26, 2012

First Cup—Poetry Friday

What: is a poem?

An explosion in a silent movie,

muted, stretching to say more

than can be said

visually; incomplete missing

something but some how saying

more;

A rose from which the petals

have fallen, on the ground,

somehow connected

though fallen—still in

the picture;

A silent long and wordless sigh

reaching deeper than

yesterday

An acute angel of vision

seeing less but differently

angled into insight, however

personal and limited and more

A word that stands alone

calling attention to its

sound, discrete and personal

singing its own song for itself

and others with ears to

hear

an image starkly lighted

yet private

inviting to those brave enough

to hear or see or

both.

(a scream on the edge

Of a bridge—

the sky orange)

—amk

An explosion in a silent movie,

muted, stretching to say more

than can be said

visually; incomplete missing

something but some how saying

more;

A rose from which the petals

have fallen, on the ground,

somehow connected

though fallen—still in

the picture;

A silent long and wordless sigh

reaching deeper than

yesterday

An acute angel of vision

seeing less but differently

angled into insight, however

personal and limited and more

A word that stands alone

calling attention to its

sound, discrete and personal

singing its own song for itself

and others with ears to

hear

an image starkly lighted

yet private

inviting to those brave enough

to hear or see or

both.

(a scream on the edge

Of a bridge—

the sky orange)

—amk

Sunday, October 21, 2012

Second Cup—Sunday

WHO WILL SUFFER WITH THE SAVIOR?

• Isaiah 53:4-12

• Psalm 91:9-16

• Hebrews 5:1-10

• Mark 10:35-45

The theme of suffering runs pretty much throughout the readings for this 21st Sunday after Pentecost—a theme I’d just as soon not have to think about. Psalm 91 seems to be in contrast to the other three; however, the other three are pretty much undeniably about the redemptive power of suffering.

The Isaiah passage is more often than not connected to Jesus; I get that—it is easy to read Jesus back into this text. (Well, most of the text; there are a few passages that have to be ignored. I understand why the church read Jesus back into the text and concluded that this is Messianic prophecy.) I think, however, that we do that at some risk to ourselves. That reading allows me not to think about what it means for me, my life, and the redemption of the world.

I think that this reading is really about Israel and, by extension, the church. Another way to say that is this passage is about the people of God in the world for the world. The heading reads “a light to the nations.” That’s one of the themes that Israel—and, again, by extension, the church—is uncomfortable with. We like the chosen part; we do not like the light on the hill bit, unless it means that the world can see how wonderful we are, how right we are, and how powerful we are.

The suffering of Jesus can be redemptive—“Behold, the Lamb of God Who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29) and "... the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world" (Revelation 13:8). OK. We get that: there is benefit to that. But us? But me? Suffering servants?! Suffering servant?! Getting a bit uncomfortable now.

Yet, Jesus says to his disciples who ask for positions of power and authority in the kingdom, “Can you drink from the cup from which I will drink? Can you be baptized with the baptism with which I will be baptized?” Whew! Hard questions: always hard questions. I think I have grown soft. I think I am cowardly. I think I am afraid of suffering—suffering for me, let alone for anyone else. But Jesus suffered for me—his great sacred heart was broken for me. His love for me—and all humankind—was so wide and deep and high and full and rich that he died rather than give me—give us—up. Can I drink from the cup from which he drank? Can I be baptized with his baptism? It is certainly my question and one I will live with and into. It is also the question for the church.

If the church is the body of Christ, where are the wounds?

• Isaiah 53:4-12

• Psalm 91:9-16

• Hebrews 5:1-10

• Mark 10:35-45

The theme of suffering runs pretty much throughout the readings for this 21st Sunday after Pentecost—a theme I’d just as soon not have to think about. Psalm 91 seems to be in contrast to the other three; however, the other three are pretty much undeniably about the redemptive power of suffering.

The Isaiah passage is more often than not connected to Jesus; I get that—it is easy to read Jesus back into this text. (Well, most of the text; there are a few passages that have to be ignored. I understand why the church read Jesus back into the text and concluded that this is Messianic prophecy.) I think, however, that we do that at some risk to ourselves. That reading allows me not to think about what it means for me, my life, and the redemption of the world.

I think that this reading is really about Israel and, by extension, the church. Another way to say that is this passage is about the people of God in the world for the world. The heading reads “a light to the nations.” That’s one of the themes that Israel—and, again, by extension, the church—is uncomfortable with. We like the chosen part; we do not like the light on the hill bit, unless it means that the world can see how wonderful we are, how right we are, and how powerful we are.

The suffering of Jesus can be redemptive—“Behold, the Lamb of God Who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29) and "... the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world" (Revelation 13:8). OK. We get that: there is benefit to that. But us? But me? Suffering servants?! Suffering servant?! Getting a bit uncomfortable now.

Yet, Jesus says to his disciples who ask for positions of power and authority in the kingdom, “Can you drink from the cup from which I will drink? Can you be baptized with the baptism with which I will be baptized?” Whew! Hard questions: always hard questions. I think I have grown soft. I think I am cowardly. I think I am afraid of suffering—suffering for me, let alone for anyone else. But Jesus suffered for me—his great sacred heart was broken for me. His love for me—and all humankind—was so wide and deep and high and full and rich that he died rather than give me—give us—up. Can I drink from the cup from which he drank? Can I be baptized with his baptism? It is certainly my question and one I will live with and into. It is also the question for the church.

If the church is the body of Christ, where are the wounds?

Friday, October 19, 2012

First Cup--Poetry Friday

This poem was written a few years back when Judy and I were on a trip in and around Massachusetts. We visited Walden Pond and Concord—truly lovely rich spots. We wondered around in the Bronson Alcott's school/barn where folks like Emerson, Julia Ward Howe, and William James taught.

These Concord men and women

challenge me soul deep.

These self-determining, garden-tending,

child-begetting, paradigm-upsetting,

idea-formulating, barn-schooling.

wood-chopping philosophers--

searchers for the Oversoul in their own backyards.

These talkers, endless explorers, ever vergent.

These walkers in the woods.

These self-reliant connoisseurs and teachers.

These hardy loners, poets, novel writers.

These coffee chatting neighbors.

These book devourers, book producers.

These transcenders.

These endlessly speaking

men and women,

genteel in their dress,

wildly improper in their minds.

These desirers of greatness, certain

of their right to be great.

These influencers; these builders

of schools and systems,

of ideas and houses and cabins.

These Concord men and women

challenge me soul deep.

—amk (2006)

Monday, October 15, 2012

First Cup--Sunday (yesterday)

Lectionary Sunday

Amos 5:6-7, 10-15

Psalm 90: 12-17

Hebrews 4:12-16

Mark 10:17-31

“Hope is believing in God’s future now; faith is dancing to it.”

That calligraphic statement hangs in our dining room just above the buffet and below the teacup rack and to the north of two other statements—these other two are biblical.

“Do not be afraid. I have redeemed you. I have called you by your name. You are mine. You are precious in my eyes and honored and I love you.” —Isaiah

“This is what Yahweh asks of you, only this: to act justly to love tenderly and to walk humbly with your God.” —Micah

These three powerful statements are rich with hope—a hope that is founded, rooted, cemented in the deep and relational and unrelenting inexplicable lovetowardus of God. And, while these passages are moving and reassuring, they are not finally not warm and fuzzy. As Hebrews tells us, God’s word is sharp and dividing and active and piercing and discriminating—hard, in another word. Hard.

“You are mine”—Good, right? The Creator God of the universe owns me. Oh.

“Only this: justice, love, humility”—Good, right. That’s it? That’s all? Only justice, love, and humility. Oh.

Today’s lections are also full of hope—and other ideas:

Justice—always justice. This God nags about justice. “…how monstrous [are] your sins; you bully the innocent, extort ransoms, and in court push the destitute out of the way.”

Economics—justice is so often referenced in economic terms: the hard economics of God. Wealth, always in the way. “One thing you lack: go, sell everything you have, and give to the poor….”

Mortality—that ultimate fact we work so hard to ignore: we die: “So make us know how few are our days, that our minds may learn wisdom.” Wisdom: always hard earned.

Doom—never seems too far away; the unintended consequence of our refusal to do justice. Unintended for us who forget about justice.

And hope—

It is a hard hope we are called to—in the midst of our humanity, our willfulness, our lustfulness, our selfishness. We are called to believe in the world God dreams for us—and, then, to act as if it is already true, even as we see that the world, as lovely as it is, is full of pain and injustice. It is not an easy dance we are called to and more often than not it is not a graceful dance (however grace-filled it may be). We are not practiced at it. We are more like the good young man Jesus meets and says, Leave it all to the those that really need it and come, dance with me. I think the look on Jesus’ face as the young man walks slowly and sadly away is the look he often has as he watches me, turn and walk away.

Amos 5:6-7, 10-15

Psalm 90: 12-17

Hebrews 4:12-16

Mark 10:17-31

“Hope is believing in God’s future now; faith is dancing to it.”

That calligraphic statement hangs in our dining room just above the buffet and below the teacup rack and to the north of two other statements—these other two are biblical.

“Do not be afraid. I have redeemed you. I have called you by your name. You are mine. You are precious in my eyes and honored and I love you.” —Isaiah

“This is what Yahweh asks of you, only this: to act justly to love tenderly and to walk humbly with your God.” —Micah

These three powerful statements are rich with hope—a hope that is founded, rooted, cemented in the deep and relational and unrelenting inexplicable lovetowardus of God. And, while these passages are moving and reassuring, they are not finally not warm and fuzzy. As Hebrews tells us, God’s word is sharp and dividing and active and piercing and discriminating—hard, in another word. Hard.

“You are mine”—Good, right? The Creator God of the universe owns me. Oh.

“Only this: justice, love, humility”—Good, right. That’s it? That’s all? Only justice, love, and humility. Oh.

Today’s lections are also full of hope—and other ideas:

Justice—always justice. This God nags about justice. “…how monstrous [are] your sins; you bully the innocent, extort ransoms, and in court push the destitute out of the way.”

Economics—justice is so often referenced in economic terms: the hard economics of God. Wealth, always in the way. “One thing you lack: go, sell everything you have, and give to the poor….”

Mortality—that ultimate fact we work so hard to ignore: we die: “So make us know how few are our days, that our minds may learn wisdom.” Wisdom: always hard earned.

Doom—never seems too far away; the unintended consequence of our refusal to do justice. Unintended for us who forget about justice.

And hope—

It is a hard hope we are called to—in the midst of our humanity, our willfulness, our lustfulness, our selfishness. We are called to believe in the world God dreams for us—and, then, to act as if it is already true, even as we see that the world, as lovely as it is, is full of pain and injustice. It is not an easy dance we are called to and more often than not it is not a graceful dance (however grace-filled it may be). We are not practiced at it. We are more like the good young man Jesus meets and says, Leave it all to the those that really need it and come, dance with me. I think the look on Jesus’ face as the young man walks slowly and sadly away is the look he often has as he watches me, turn and walk away.

Saturday, October 13, 2012

First cup--Saturday

I think everyone knows first person personal confessional autobiography is not a new genre. The use of prose and poetry to think and reflect on one’s life—a kind of public journal—dates back, at least, to Augustine Confessions. I think the first time I became really aware of this genre was when I read Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain, although the writings of Loren Eiseley actually predate that.

Over the years, many persons have invited me into their lives and their reflections on their lives through such writings. I know that many novels are cloaked autobiography—sometimes it is simply easier that way. The facts can be bent and rearranged and it is always possible to say, well, no, it’s not my story; remember it’s a novel.

I think, however, that the 20th century has been full of such autobiographical and semi-autobiographical work. As I look over the shelves of my library, I see Madeleine L’Engle, Anne Dillard, Kathleen Norris, Fredric Buechner, Stanley Hauwerwas,Henri Nouwen, Parker Palmer, Philip Yancey, Mel White, William Sloan Coffin, Barry Lopez, C.S. Lewis, Bruce Feiler; I remember clearly the moving reflections on life and science in the writings of Loren Eiseley; and, of course, there are the diaries of Thomas Merton—and his ageless (however dated) classic The Seven Storey Mountain. Don Miller’s books and Anne Lamott’s are recent additions to this list. There are more; too many to list here, although these are the writers whose narratives have moved and challenged and directed me on my own journey.

L’Engle’s Crosswick’s Journals came into my world at important points in my own journey and struggle. The Summer of the Great Grandmother came when we were working through the Alzheimer’s and dementia of my parents; her Two-Part Invention, the story of a marriage recounting her marriage and the journey with her husband’s death provided a profound means of dealing with my own grief at the dying of those same parents—and helped me, perhaps for the first time, to address my own mortality. The freshness of Kathleen Norris’ journey from Bennington to Dakota and into the monastic spirit helped me think about my own journey with the church and mental and spiritual health while I was walking my way to the light guided by my Mary. I don't think I could ever adequately explain the enlightening power of The Seven Storey Mountain—a journey so radically different from and, enigmatically, so much the same as my own.

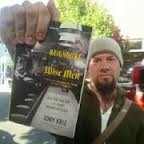

In the last few days, I’ve added another to this list: Tony Kriz’s Neighbors and Wise Men, a book I might never have noticed had the author not been another of WPC’s “senior adjunct professors.” A doctor in spiritual formation, Tony’s journey from what I would call the dark certainty of fundamentalism to the light uncertainty of relational faith and the lightly held but no less deep convictions and practices of a follower of Jesus is a wonderful confessional journal. It speaks humbly and relationally and invitationally—I guess, I mean incarnationally.

So many people are confused about this idea of “hearing from God.” Many believe that God does speak—we confess it. Yet, frankly, so few understand how. By Tony’s willingness to pay attention to what is going on around him, to the words of the people who talk to him (whether Muslims in Albania or bartenders in Portland), to the stories recorded in scripture, and to what all of this stirs up in him—this latter is in many ways the most important. To not run from the discomfort, the anguish, the uncertainty; to not escape into the old and glib oh-so-easy answers and to, one step at a time, engage what is stirring. It is in such difficult and emotionally trying times that God shows up. One of the amazing biblical pictures of God is when God shows up in a whirlwind. Think about it: here is a man named Job whose life has gone completely and wildly out of control, even as he asserts again and again that the old verities do not explain this out-of-controlness. What is needed here is the God “who makes me to lie down in green pastures” and who vindicates me; instead: whirlwind. That’s the God we don’t like; the God we run from—the God who doesn’t remove us from “the valley of the shadow of death” but is in the valley with us and whose presence is not always comforting or comfortable.

This is the value of this book: unstinting courage in the face of God’s uncomfortable, enigmatically relational creativity; the God who is with us but not in the platitude, no, in the whirlwind. Tony’s honest journey with God and others challenges and inspires. The narrative heart of the book is found near the end of it in a description of another person—Bobbin: “He busted down the door. He busted it with silence, with listening, with humility, with contrition and remorse…at least for one conversation. And sometimes one conversation can change your life” (Kriz, Tony. (2012) Neighbors and Wise Men, sacred encounters in a Portland pub and other unexpected places. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 221).

Over the years, many persons have invited me into their lives and their reflections on their lives through such writings. I know that many novels are cloaked autobiography—sometimes it is simply easier that way. The facts can be bent and rearranged and it is always possible to say, well, no, it’s not my story; remember it’s a novel.

I think, however, that the 20th century has been full of such autobiographical and semi-autobiographical work. As I look over the shelves of my library, I see Madeleine L’Engle, Anne Dillard, Kathleen Norris, Fredric Buechner, Stanley Hauwerwas,Henri Nouwen, Parker Palmer, Philip Yancey, Mel White, William Sloan Coffin, Barry Lopez, C.S. Lewis, Bruce Feiler; I remember clearly the moving reflections on life and science in the writings of Loren Eiseley; and, of course, there are the diaries of Thomas Merton—and his ageless (however dated) classic The Seven Storey Mountain. Don Miller’s books and Anne Lamott’s are recent additions to this list. There are more; too many to list here, although these are the writers whose narratives have moved and challenged and directed me on my own journey.

L’Engle’s Crosswick’s Journals came into my world at important points in my own journey and struggle. The Summer of the Great Grandmother came when we were working through the Alzheimer’s and dementia of my parents; her Two-Part Invention, the story of a marriage recounting her marriage and the journey with her husband’s death provided a profound means of dealing with my own grief at the dying of those same parents—and helped me, perhaps for the first time, to address my own mortality. The freshness of Kathleen Norris’ journey from Bennington to Dakota and into the monastic spirit helped me think about my own journey with the church and mental and spiritual health while I was walking my way to the light guided by my Mary. I don't think I could ever adequately explain the enlightening power of The Seven Storey Mountain—a journey so radically different from and, enigmatically, so much the same as my own.

In the last few days, I’ve added another to this list: Tony Kriz’s Neighbors and Wise Men, a book I might never have noticed had the author not been another of WPC’s “senior adjunct professors.” A doctor in spiritual formation, Tony’s journey from what I would call the dark certainty of fundamentalism to the light uncertainty of relational faith and the lightly held but no less deep convictions and practices of a follower of Jesus is a wonderful confessional journal. It speaks humbly and relationally and invitationally—I guess, I mean incarnationally.

So many people are confused about this idea of “hearing from God.” Many believe that God does speak—we confess it. Yet, frankly, so few understand how. By Tony’s willingness to pay attention to what is going on around him, to the words of the people who talk to him (whether Muslims in Albania or bartenders in Portland), to the stories recorded in scripture, and to what all of this stirs up in him—this latter is in many ways the most important. To not run from the discomfort, the anguish, the uncertainty; to not escape into the old and glib oh-so-easy answers and to, one step at a time, engage what is stirring. It is in such difficult and emotionally trying times that God shows up. One of the amazing biblical pictures of God is when God shows up in a whirlwind. Think about it: here is a man named Job whose life has gone completely and wildly out of control, even as he asserts again and again that the old verities do not explain this out-of-controlness. What is needed here is the God “who makes me to lie down in green pastures” and who vindicates me; instead: whirlwind. That’s the God we don’t like; the God we run from—the God who doesn’t remove us from “the valley of the shadow of death” but is in the valley with us and whose presence is not always comforting or comfortable.

This is the value of this book: unstinting courage in the face of God’s uncomfortable, enigmatically relational creativity; the God who is with us but not in the platitude, no, in the whirlwind. Tony’s honest journey with God and others challenges and inspires. The narrative heart of the book is found near the end of it in a description of another person—Bobbin: “He busted down the door. He busted it with silence, with listening, with humility, with contrition and remorse…at least for one conversation. And sometimes one conversation can change your life” (Kriz, Tony. (2012) Neighbors and Wise Men, sacred encounters in a Portland pub and other unexpected places. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 221).

Friday, October 12, 2012

Poetry Friday

This morning I went looking for an old file of my poems; it took awhile to find it, tucked away in the back of the second drawer of my filing cabinet. Not in alphabetical position. I wonder how it got out of order—isn’t that just like poetry: never where you expect it to be. Yet, while I was looking for it, I thought, I haven’t had a new poem since back in June. Wonder why that is. Too busy? Probably. Not enough time just sitting a staring? Likely. No rain—yes, here, that would be the case; something about the rain that brings out the soul. After so many months of lovely sunny weather, Oregon seems to be back today and the weather experts are saying that it will be around for a while. Perhaps as the soil is watered so my soul will.

Searching back through my journal, I found this, dated June 2 and situated at the Benedictine Monastery, Mt. Angel. It is titled “Halfway to 70.” A momento mori.

Born in 1943, January,

I am 69. It is June.

Month six. Halfway to 70.

It occurs to me that halfway

is an apt metaphor of my life.

Standing in a door—the door

I’ve so often described to my

students: the door of life.

Of decision. Irrevocable. It

has a door knob on the

enter side—and nonesuch

on the other. If it shuts

behind, there you are.

Shut in front, there is

always the possibility that you

could open it again.

I stand in the doorway. Neither

in nor out. Some might call it

liminal space—all such times have

been times of potential. But

more like cowardice for me.

I’ve almost let it close behind

me. More than once. Never really,

though. At last moment, finger tips

gripping, I open it and

step back in.

Those who can’t, teach.

Perhaps.

Perhaps it is that I am a

doorkeeper meant to keep it

open? To live on the verge.

In this space. To show others

the way through. Someone has to

be a doorkeeper.

That would be good;

If only it is true

Thursday, October 11, 2012

Future story

In a recent presidential newsletter, In the City, President Cook wrote about her opportunity to serve on the Ministries Council of the Church of God, Anderson. She points out that “The church is undergoing a critical moment of transition” related to the search for a new General Director and is doing serious work about the future. She writes that she has also “been facilitating a committee that has been tasked to write a ‘Future Story’ that will articulate ‘what the Church of God will look like in 2023’” (In the City, September 2012).

I am taken by this idea: writing / describing / illustrating / imagining what the future might look like—what we want it to look like—what we hope it will look like. It is a hopeful idea: there just might be a future. It’s a bridge—at least, that is what I’m reading about future stories: a bridge rooted in the bedrock of the past yet stretching toward the future. Yes, I know, no one can predict that; God happens; life happens; stuff happens, as they say; change is constant, at least that’s what people have been saying since Heraclitus; yet there is something hopeful about the idea. And hope is good.

I’ve been thinking about all this; I’ve been thinking that it might be an interesting ending activity for Hum 310 or Rel 320—after all of this reading and talking and reflecting, write your future. I’ve been thinking that, perhaps, I might write my own. As short term as my future may be, I am hopeful. Most of me is working pretty well—at least, no one has said, “Say, Arthur, could I talk to you about what you…….”

Mostly, however, I’m thinking about the future of Warner Pacific College and about the future of the Church of God reformation movement and about how those two futures intertwine. What is the story our gang of futurists is writing? Who are they, by the way, and why are they the ones who are doing this? Is there a historian among them? What qualifications are necessary to be a futurist? Are they all churchmen, church women, bureaucrats; is there a poet among them? Surely, in some sense, writing the future is writing a poem. What is their demographic—age, gender, ethnicity, geography, and so on? Will we get to vote on our future? Maybe, most importantly, are they people formed by the narrative of this particular and peculiar group of persons—or is their formation along other plot lines? And, then, there is that other question— What if I/we don’t like the story they are writing?

But the question I’m most concerned about is the penultimate one on that list. I’m not sure why we do this, but it seems to me that one way to read our history is that we spend more time listening to other narratives than we do to our own. With the exception, perhaps, of the earliest formational days of the church when a radically different idea was preached, we have often (more often?) listened to other narratives. I think there was a period in the corporate life of the church when the dominative narrative was the narrative of corporate culture—that may be the most dominant parallel narrative. Many, for example, were convinced that the narrative of General Motors was the one we needed to live. I think we embraced a narrative of power (perhaps even of fear) when we decided that the General Assembly should be molded along lines that inhibited rather than permitted dialogue and argument and conversation and mutual discovery and, yes, accountability.

I think the restructuring that resulted in Church of God Ministries—and the struggle we continue to have with it and its relevance—is the result of listening to other cultural narratives: those of the church growth and mega church narratives that have so dominated the church’s conversation for the last 50 years.

Now, I do not mean to suggest that we shouldn’t know those other narratives or ask what they might have to teach us, and neither should this be construed as an argument to go back to another time. We have too many folks around who think that backwards is the direction we should head. However, says Strege, “those who are unclear in their identity can hardly be expected to know how to go forward well. Understanding the present and determining a path through the future become risky and subject to great error when divorced from historical understanding” (Strege, The Quest for Holiness and Unity, 515).

I think there are some ideas and understandings that were central to how we lived together—or, at least, how we thought and taught we should live together—that are still mighty attractive. I hope these narratives and practices are included in the plotlines of this future story.

What am I talking about?

Well, that will be a subject for another blog.

I am taken by this idea: writing / describing / illustrating / imagining what the future might look like—what we want it to look like—what we hope it will look like. It is a hopeful idea: there just might be a future. It’s a bridge—at least, that is what I’m reading about future stories: a bridge rooted in the bedrock of the past yet stretching toward the future. Yes, I know, no one can predict that; God happens; life happens; stuff happens, as they say; change is constant, at least that’s what people have been saying since Heraclitus; yet there is something hopeful about the idea. And hope is good.

I’ve been thinking about all this; I’ve been thinking that it might be an interesting ending activity for Hum 310 or Rel 320—after all of this reading and talking and reflecting, write your future. I’ve been thinking that, perhaps, I might write my own. As short term as my future may be, I am hopeful. Most of me is working pretty well—at least, no one has said, “Say, Arthur, could I talk to you about what you…….”

Mostly, however, I’m thinking about the future of Warner Pacific College and about the future of the Church of God reformation movement and about how those two futures intertwine. What is the story our gang of futurists is writing? Who are they, by the way, and why are they the ones who are doing this? Is there a historian among them? What qualifications are necessary to be a futurist? Are they all churchmen, church women, bureaucrats; is there a poet among them? Surely, in some sense, writing the future is writing a poem. What is their demographic—age, gender, ethnicity, geography, and so on? Will we get to vote on our future? Maybe, most importantly, are they people formed by the narrative of this particular and peculiar group of persons—or is their formation along other plot lines? And, then, there is that other question— What if I/we don’t like the story they are writing?

But the question I’m most concerned about is the penultimate one on that list. I’m not sure why we do this, but it seems to me that one way to read our history is that we spend more time listening to other narratives than we do to our own. With the exception, perhaps, of the earliest formational days of the church when a radically different idea was preached, we have often (more often?) listened to other narratives. I think there was a period in the corporate life of the church when the dominative narrative was the narrative of corporate culture—that may be the most dominant parallel narrative. Many, for example, were convinced that the narrative of General Motors was the one we needed to live. I think we embraced a narrative of power (perhaps even of fear) when we decided that the General Assembly should be molded along lines that inhibited rather than permitted dialogue and argument and conversation and mutual discovery and, yes, accountability.

I think the restructuring that resulted in Church of God Ministries—and the struggle we continue to have with it and its relevance—is the result of listening to other cultural narratives: those of the church growth and mega church narratives that have so dominated the church’s conversation for the last 50 years.

Now, I do not mean to suggest that we shouldn’t know those other narratives or ask what they might have to teach us, and neither should this be construed as an argument to go back to another time. We have too many folks around who think that backwards is the direction we should head. However, says Strege, “those who are unclear in their identity can hardly be expected to know how to go forward well. Understanding the present and determining a path through the future become risky and subject to great error when divorced from historical understanding” (Strege, The Quest for Holiness and Unity, 515).

I think there are some ideas and understandings that were central to how we lived together—or, at least, how we thought and taught we should live together—that are still mighty attractive. I hope these narratives and practices are included in the plotlines of this future story.

What am I talking about?

Well, that will be a subject for another blog.

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

My books and me....spiritual formation

In class, recently, I said, "I've always been a reader; I honestly cannot remember when I didn't read." Of course, there was a time before I could read, but I have always been surrounded by books. We had books in the house I grew up in and, most importantly, within walking distance was the Julia C. Lathrop Branch Library, located in a wing of the Julia C. Lathrop Junior High School, where I would spend two horrible and one pretty amazing years.

Why am I writing about this today? Well, one of the books I'm reading right now is Tony Kriz's Neighbors and Wise Men—more about that when I've finished it. However, the chapter on spiritual formation got me to thinking about the neighborhood I grew up in, a neighborhood that contained, within walking distance, the Lathrop Branch Library and the wonderful women who worked there who were my guides into the world of books. I still remember Miss Calkins, Leona; she was the boss. A formidable woman who loved books and loved introducing people to books. I could describe this place to you in vivid detail. I spent so many hours there; it was also the location of my first job—imagine that?! I worked in a place I loved. (Actually, pretty much, I can say that about all the places I've worked.)

One powerful memory: the library had four rooms: the main reading and reference room, the adult reading room, the children's room, and the young reader's room. Dark wooden shelves from floor to ceiling; half way up was a shelf. I am following Miss Calkins along that wall as she pulls book after book, sets them on the shelf, saying, "Read this!" Thank you, Miss Calkins! I read them all--most of them, unabridged.

Who knows how many books I've read? I keep a record now, but that might cover only the last ten years or so. What does this have to do with spiritual formation? Well, for me, everything. I love people and have clearly been blessed to be in relationship with wonderful folks who have thought long about what it means to be Jesus follower--and who have tried to live what they thought. Sometime, perhaps, I'll write about those folks. But books have been the voice of God for me. All kinds of books. Not talking only about religious or Christian books--the truth is that there would probably be fewer of them than others. I love novels and I read more novels than anything else. I love theology, too, and novels provide a kind of commentary on theology--much the way that biblical stories are the heart of Scripture.

Last night I finished Michael Gruber's The Book of Air and Shadows. It's a literary mystery developed around one of the great mysteries of English literature--why don't we know more about and have more evidence that Shakespeare actually wrote the plays that bear his name? A contemporary coded set of letters in found bound into the covers of an old book; the set of letters talk about a Mr. W. S. and a seditious play that he has been tricked into writing--all set in the religious struggles of pre-reformation England. Is it possible that W.S. is William Shakespeare and is it possible that there exists a new play, extant, that can clearly and finally be linked to Shakespeare--and, thereby, resolve hundreds of years of scholarship? Well, I won't tell you how it ends (no spoiler alert); but it involves transcontinental travel, the "mob" in various forms and moralities, kidnapping, thugs, international copyright laws, scholarly reputations and, possibly, wealth.

It is a lovely read, but what does it have to do with spiritual formation? A long, loving, honest look into the human condition and the state of the soul. The possibility of redemption. A thoughtful consideration of the relationship between violence and redemption--and the American psyche. Human genius and human duplicity. Sometimes I think it would be better for all of us if we treated the Bible like a novel. Sometimes sacred texts are so sacred that we miss out on the humanity. Sometimes we think that the suffering of Jesus wasn't real suffering--a form of gnosticism. Novels help me to understand that humans are capable of many wonderful things and, yes, redeemable (thank God!); but that we are also capable of really horrible things and are more than able (and sometimes more than willing) to inflict those really horrible things on others--and, yes, even the most loving one who ever walked the face of the earth.

So, thank you, Miss Calkins and Betty Wimpress, for being two of the most important of my spiritual guides along my pilgrim way. And, thank you, Mom and Dad, for encouraging me to read and never really keeping me from reading anything I put my hands on.

Why am I writing about this today? Well, one of the books I'm reading right now is Tony Kriz's Neighbors and Wise Men—more about that when I've finished it. However, the chapter on spiritual formation got me to thinking about the neighborhood I grew up in, a neighborhood that contained, within walking distance, the Lathrop Branch Library and the wonderful women who worked there who were my guides into the world of books. I still remember Miss Calkins, Leona; she was the boss. A formidable woman who loved books and loved introducing people to books. I could describe this place to you in vivid detail. I spent so many hours there; it was also the location of my first job—imagine that?! I worked in a place I loved. (Actually, pretty much, I can say that about all the places I've worked.)

One powerful memory: the library had four rooms: the main reading and reference room, the adult reading room, the children's room, and the young reader's room. Dark wooden shelves from floor to ceiling; half way up was a shelf. I am following Miss Calkins along that wall as she pulls book after book, sets them on the shelf, saying, "Read this!" Thank you, Miss Calkins! I read them all--most of them, unabridged.

Who knows how many books I've read? I keep a record now, but that might cover only the last ten years or so. What does this have to do with spiritual formation? Well, for me, everything. I love people and have clearly been blessed to be in relationship with wonderful folks who have thought long about what it means to be Jesus follower--and who have tried to live what they thought. Sometime, perhaps, I'll write about those folks. But books have been the voice of God for me. All kinds of books. Not talking only about religious or Christian books--the truth is that there would probably be fewer of them than others. I love novels and I read more novels than anything else. I love theology, too, and novels provide a kind of commentary on theology--much the way that biblical stories are the heart of Scripture.

Last night I finished Michael Gruber's The Book of Air and Shadows. It's a literary mystery developed around one of the great mysteries of English literature--why don't we know more about and have more evidence that Shakespeare actually wrote the plays that bear his name? A contemporary coded set of letters in found bound into the covers of an old book; the set of letters talk about a Mr. W. S. and a seditious play that he has been tricked into writing--all set in the religious struggles of pre-reformation England. Is it possible that W.S. is William Shakespeare and is it possible that there exists a new play, extant, that can clearly and finally be linked to Shakespeare--and, thereby, resolve hundreds of years of scholarship? Well, I won't tell you how it ends (no spoiler alert); but it involves transcontinental travel, the "mob" in various forms and moralities, kidnapping, thugs, international copyright laws, scholarly reputations and, possibly, wealth.

It is a lovely read, but what does it have to do with spiritual formation? A long, loving, honest look into the human condition and the state of the soul. The possibility of redemption. A thoughtful consideration of the relationship between violence and redemption--and the American psyche. Human genius and human duplicity. Sometimes I think it would be better for all of us if we treated the Bible like a novel. Sometimes sacred texts are so sacred that we miss out on the humanity. Sometimes we think that the suffering of Jesus wasn't real suffering--a form of gnosticism. Novels help me to understand that humans are capable of many wonderful things and, yes, redeemable (thank God!); but that we are also capable of really horrible things and are more than able (and sometimes more than willing) to inflict those really horrible things on others--and, yes, even the most loving one who ever walked the face of the earth.

So, thank you, Miss Calkins and Betty Wimpress, for being two of the most important of my spiritual guides along my pilgrim way. And, thank you, Mom and Dad, for encouraging me to read and never really keeping me from reading anything I put my hands on.

Sunday, October 7, 2012

Friday, October 5, 2012

Morning Joe--Poetry Friday

This poem grows from participation in a Godly Play "wondering"

based on the story of the Great Shepherd and the sheep—a story

that is one of the Jesus stories that never fails to move me. Never.

Olly olly oxen free free free

We hide; he seeks.

He seeks; we run away.

He runs after, gives chase,

calling after us, coaxing us;

We say, What do you want?

He says, Olly olly oxen free free free

He hides; we seek.

He’s found; we’re surprised.

We cover him, hoping he’ll stay hidden

but we’re drawn back and check.

Yes, he’s still there, smiling;

We say, What do you want?

He says, Olly olly oxen free free free

He plays and calls us to play,

to sit with him on the ground,

clothes dusty, knees worn;

We say, What do you want?

He says, Look there’s a box.

Pandora’s? Well, maybe, but God’s, for sure.

Careful, parable at work. Lift the lid, open the present,

look inside:

A sheepfold holding—I wonder.

A quiet seed growing—I wonder.

A whole universe becoming—I wonder.

A mystery—a silent child speaking loudly

in our circle—the face of the child is the

Face of God we can see

and the child, in a quiet and holy space,

humming a tune:

Olly olly oxen free free free

Follow me, the Shepherd says, over the grass,

by the pond, through the rocks

to the golden nest in the mustard tree

under the shining sun

singing a song

Olly olly oxen free free free

—amk

Monday, October 1, 2012

First cup—Sunday morning

An amazing, sweet, delightful conversation

• Numbers 11:4-6, 10-16, 24-29

• Psalm 19:7-14

• James 5:13-20

• Mark 9:38-50

There are weeks in the lectionary when the readings hang together in obvious ways with clear connections. The conversation among the readings and the manner in which they talk about, comment on, and speak to each other is transparent. Then, there are other weeks when the response is “Huh? What in the world did these folks have in mind when they brought these readings into the same room?!”

It was that kind of week for me—at least, initially.

The problem for people like me who were not raised with the lectionary is that I keep forgetting the big picture. The big picture is represented by the Christian calendar. These are not random passages chosen to fill blanks on a chart; they are prayerfully selected readings that fit into a larger scheme. I think also that we tend to forget the historical context as well.

(Far too many of us free church Protestants were raised in “Bible believing churches” that acted as if there were only a few passages that we preached about, taught about—maybe even knew about—most of those were Pauline, and most of those operated in some weird kind of ahistorical time. “Bible believing churches” seemed, well, selective in which part of the Bible they were going to believe—easier that way.)

So, the lections invite us to back up a bit, take another perspective, and remember that there is this calendar. It is a Christian calendar; some call it the church’s calendar. It has its own beginning and its own end that have little to do with the calendar that governs the dailiness of our lives. The latter calendar, as we all know, begins January 1 and ends December 31. The church’s calendar ends this year (Year B) on November 25 or the 26th Sunday after Pentecost or Reign of Christ Sunday; it begins (Year C) December 2 or the First Sunday of Advent.

The point of this is that Christians live in two worlds and two different perspectives—at least, we do if we hear what the lectionary and this calendar are trying to teach us. It's another kairos / chronos paradox. All of which brings us back to this week’s readings that are in the season the church named Pentecost, which begins with Pentecost Sunday and ends November 25—after which the whole cycle re-boots. In fact, November 25 is the last day of the Christian year. Sometimes we act as if the church has always had it all figured out. Why we think that is a mystery since we’ve been fighting about it all for, well, for the church, the last roughly 2000 years. We forget that something pretty dramatically different happened (Incarnation), and we forget that pretty dramatically different happening (Jesus) pretty much upset the whole apple cart.

What began then is an on-going conversation about what it means to be a follower of Jesus and what “church” means—a conversation that continues to this day and, likely, will continue, at least, to the second Advent. What we are reading in these passages today is some of that conversation—what does it mean to be the people of God? Since the Old Testament and Psalm readings are here, we should understand that also means the conversation has been going on even longer. The church puts its own spin on the conversation, but when Joshua ran to Moses and said tell them to stop it, Moses, fresh from a conversation with God, said, who am I to stop this conversation? What a strange God this one is! The Psalmist says, Oh my! Isn’t this rich? This conversation about the heart of things. And James to the church says: This is what you need to understand! Then, Jesus says to his disciples: This is what you need to understand! And they are each still at the table and we get to be there with them, marveling at the honey richness of it all—enjoying the simple truth that we are at the table with each other and Moses, the psalmist, James, and Jesus. We continue that long time conversations at table with Moses, the psalmist, James, and Jesus and say: What does this all mean? How do we live with each other as the people of God in our time and place?

When we newbies join the conversation, we start too deep and way too detailed. We want to do what we always do: argue about the details and ask the American question—what does this have to say to me?—rather than the biblical question—what does this have to do with us?

Really amazing, you know, to think of this all as a wonderful, difficult, challenging, life-giving conversation!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)